🇵🇰 What Factors Shape Education Reform in Pakistan?

Reflections from my first trip to one of the world's most important and complex education systems.

Pakistan was rocked by intense protests this week, with over 3,000 arrested. When I was there in March, thousands marched on the streets of Lahore. Many days I drove past flags waving in support of the former PM, TV crews, and streets blocked off by police with broken glass from shattered car windows.

When education experts discuss which interventions work and evidence, they often ignore these kinds of issues. But what determines whether we change a system is moments like these: when POLITICAL factors suddenly shift the landscape. Who is in power? How easy or hard it is to move around and do basic tasks like deliver textbooks? Will a window for innovation in government open or close?

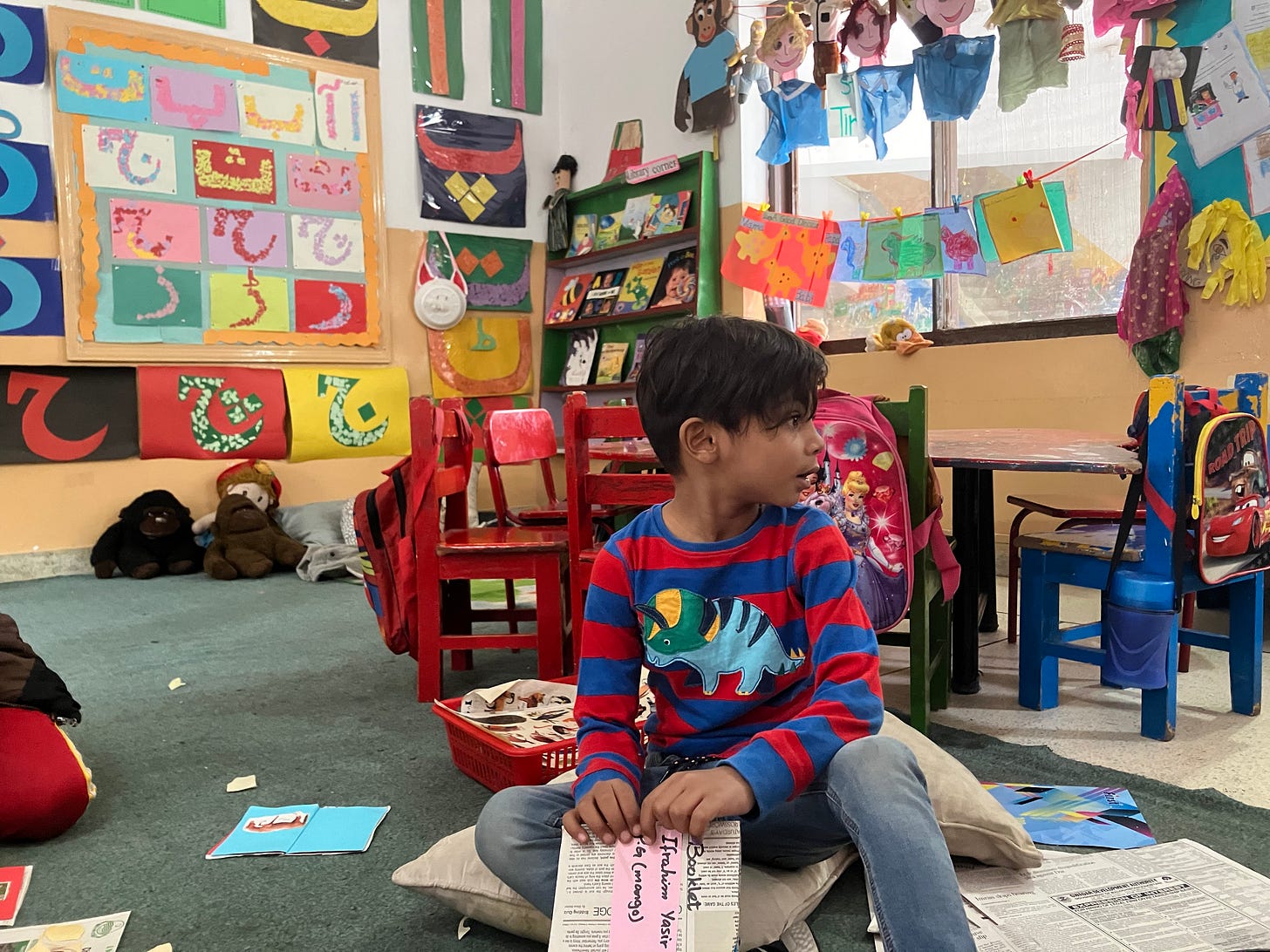

I went to Pakistan for nearly a month because even though it is the world’s 5th largest country, we don’t have enough journalism about the impressive education work happening there. As I wrote articles about the Citizens Foundation and the school founder and education expert Zubeida Mustafa, along with a forthcoming profile of the activist Baela Jamil, I visited government and private schools and met with dozens of policymakers, teachers, funders, and entrepreneurs.

There are so many heroic Pakistanis committed to changing education, and most of the time I focus on optimistic stories. But the reality is, these leaders are working in an extremely difficult environment. Here is some of what I learned - about 5 of the forces they face while trying to lead education innovation and reforms.

Did I miss something important? Please add your thoughts in the comments or hit reply!

Instability and violence make basic implementation difficult.

Too often, media in my home country (the US) only tells a negative story of Pakistan; TV shows like Homeland make it seem like the country only has terrorism, drone strikes, and CIA/ISI spies. This is a shame, because Pakistanis have more welcoming hospitality than anywhere I have ever been. There is so much more to the country than this single story.

However, war has definitely shaped the country’s trajectory. The US invasion and war in neighboring Afghanistan from 2001-2021 caused crippling violence across Pakistan, as militants from Al-Qaeda and the Taliban sought refuge in Pakistan’s border areas. Counter terrorism activities caused massive displacement.

Pakistan also has a long history of sudden shifts in political leadership and restrictions on civil society due to martial law. The first Prime Minister was assassinated in 1951. Mohammad Zia ul-Haq became President in a 1977 coup, imposed martial law, and was likely assassinated in 1988. Pervez Musharraf gained power in a 1999 coup, imposed martial law, and became PM in 2002. PM Benazir Bhutto faced an attempted coup in 1995 and was assassinated in 2007.

The reasons behind these events are complex, but overall, this political instability made it hard for leaders to sustain long-term shifts in education policies - because they were constantly dealing with urgent crises and protecting their balance of power. Though many areas of Pakistan are now safer than they were a few years ago, there are still political crises like the protests occurring right now.

Schools are a battleground for religious ideals and are shaped by patriarchy.

Pakistan is predominantly Muslim and there is a wide spectrum of types of Islam, ranging from liberal to more conservative. As Malala writes about in her memoir, in certain parts of Pakistan, the Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist group, pressured communities to remove girls from school.

Gender norms also shape who accesses education. Najma Haqnawaz, a mother in Lahore, told me how when her husband wanted their teenage daughter to marry, she and the girls’ teachers were able to convince him to postpone. But ultimately, she explained with tears in her eyes, fathers hold the power over whether their daughters stay in school.

I observed ITA lead a community meeting in a rural village. Even though the meeting discussed out-of-school girls, only male elders were present. (I was told that including women is harder to organize because in that context, women and men must be separated by a screen). This is just one example of how due to societal norms, women’s leadership is sometimes excluded from shaping issues like education. And yet, there are female activists who persist, like Malala and Baela Jamil.

Rapid inflation and natural disasters make the situation worse.

Pakistan is currently in economic crisis and inflation is at a 50-year high (36.4% in April 2023). This makes it hard for parents to afford school fees. Parents also face pressure to put their children to work to generate enough income for their family. And it is tough for education nonprofits, edtech companies, and private schools to pay salaries when the value in their bank accounts dwindles with each passing day.

Pakistan also experienced an earthquake in 2005 and devastating floods in 2010 and 2022, which destroyed many schools and infrastructure such as roads. This made it harder for students and teachers to travel to/from school and for government agencies to deliver teaching and learning materials.

However, as the wise Mosharraf Zaidi argues, there is a “unique Pakistani resilience” in the face of these obstacles. He says, a strength of “Pakistani public policy is its incredible ability to handle crises. From natural calamities to conflict…there is both human capability, organizational resourcefulness and system wide innovation that can plug the gap between where Pakistanis are, and the worst case scenarios of where they might have ended up.”

Politicians and teachers have few incentives to improve the system.

Teachers in government schools are often used for tasks that are not teaching. When I visited one government school in Karachi, 5 of the 6 teachers were out for a month on census duty. Teachers also run election poll stations and polio campaigns (the government sees them as the only source of trustworthy staff already on the payroll).

This points to a fundamental problem: even if there is a great curriculum in place or policies to train teachers well, it has little impact if students miss 6 weeks of lessons in a year because teachers are pulled out of their classrooms. Teachers are often paid bonuses to do these extra duties.

Politicians also benefit from the status quo. Some politicians own private schools and many send their own children to elite private schools (like Beaconhouse or Karachi Grammar School), so they are rarely exposed to the realities of government schools and are insulated from the effects of education reforms. For example, when all private schools were nationalized in 1972, private schools using the British system were exempt. This is probably because powerful politicians wanted to make sure their children could access a good education, even as the government systematically dismantled access to options for low-income and middle-class parents.

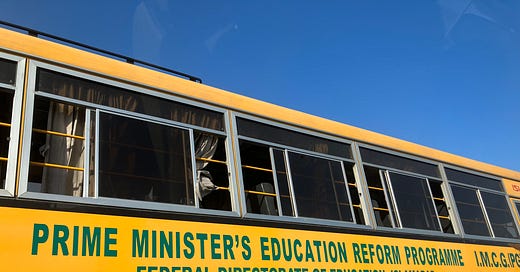

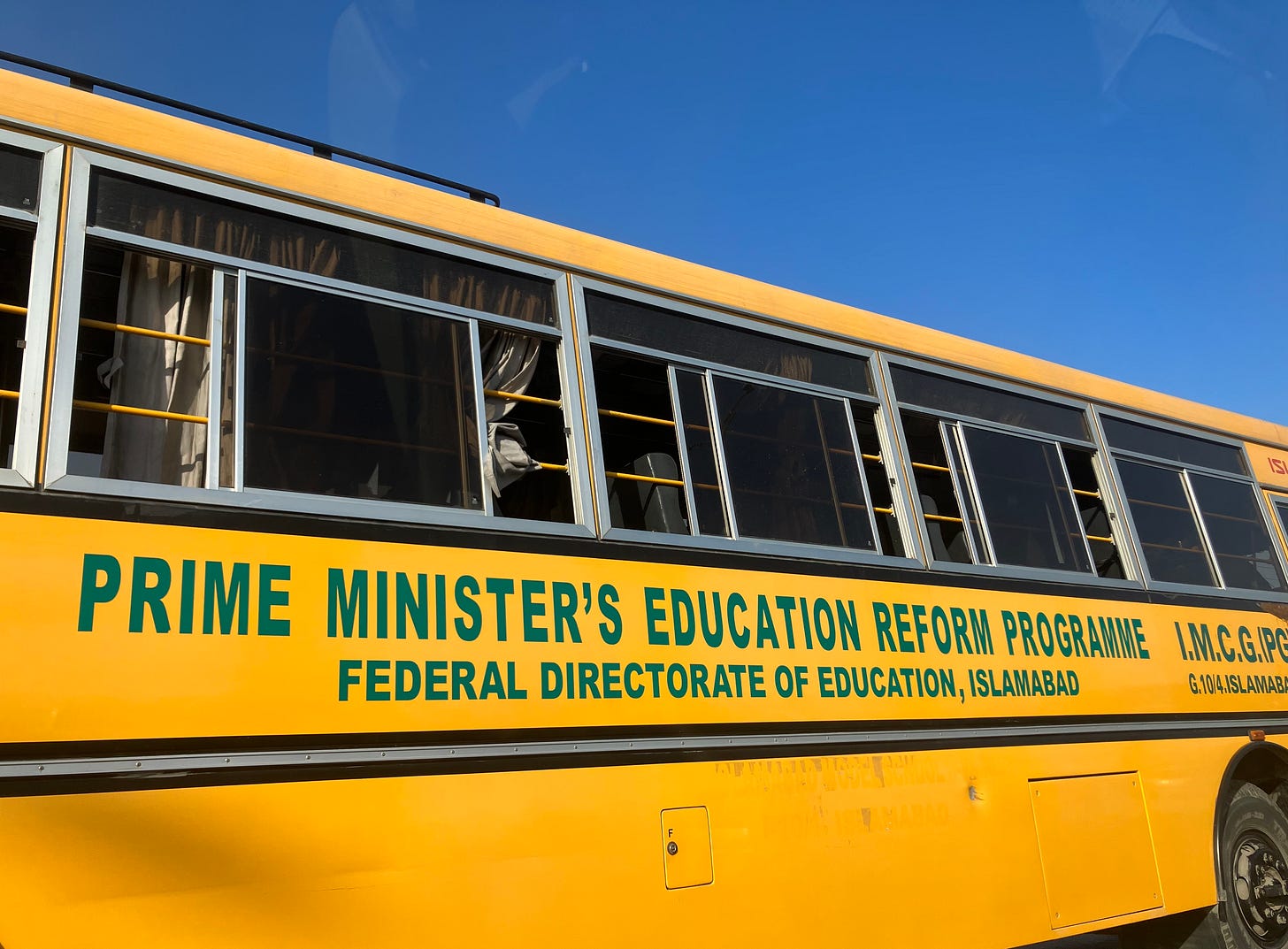

Overall, Pakistani politicians have few incentives to prioritize education reform. (Which is why it is remarkable when there are rare politicians who do, such as Shahbaz Sharif when he was Chief Minister of Punjab province).

While India gets increasing attention, Pakistan is not as prioritized globally.

As China grows its influence and India becomes the world’s most populous country, the US increasingly tries to strengthen India as an ally.

While India and China both have roughly 1.4 billion people, Pakistan also has a massive population (240 million). But it is not prioritized by many in the community of funders who support education reform worldwide. For example, while the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation granted $14.7 million to an education foundation in India, and Omidyar Network has a large education team in India, neither organization has funded education initiatives in Pakistan. These are two of the most prominent funders on education issues in low- and middle-income countries.

Perhaps some institutional funders believe that Pakistan is too difficult to work in. (One notable exception is FCDO, the UK’s development agency, which has supported many Pakistani education reforms.) As a result, it seems that it may be harder for education organizations in Pakistan to fundraise, compared to similar organizations in India.

While in Lahore, I started to understand how Pakistan’s collective memory, and its relationship with India, shapes a particular sense of national pride and identity. At the National History Museum, I experienced a VR simulation of a child during Partition in 1947. As a girl fled from India to Pakistan, she saw Muslims killed with scythes and trains filled with dead bodies roll into a station. She ran as fast as she could to cross the border area, before making it to safety. I cried as I sensed her fear.

On another day, when I went to a movie, the theatre played the Pakistani national anthem before the film started. Everyone in the audience stood and sang.

I am in awe of how out of the collective trauma of Partition and other challenges, Pakistanis became so resilient. And I am even more inspired by the many who are committed to changing education in their country.

Want to learn more? Read:

Dispatches from Pakistan - anthology on history, economics, politics.

Agents of Change: The Problematic Landscape of Pakistan’s K-12 Education & the People Leading the Change - book about TCF.

I Am Malala - memoir about advocating for girls’ education.

The Wandering Falcon - novel set in the Pakistan/Afghanistan border tribal areas.

In Other Rooms, Other Wonders - short stories about a landowner and his staff in rural Punjab.

** Bonus - listen to Coke Studio, which features Pakistan’s outstanding musicians! **

This article is based on my visits to government schools in rural and urban areas, private schools (run by TCF, Sanjan Nagar, Harsukh and Zindagi), and many of ITA’s programs. I met entrepreneurs like the Co-founder of Taleemabad, joined a conference in Islamabad about Pakistan’s ed reforms, and observed meetings with government officials from Punjab and Sindh provinces, the National Assembly, and the world’s largest ed PPP (Punjab Education Foundation). All photos taken by the author.

🌍 This is part of my journey to write a book about systems change leaders in the Global South's education bright spots (Brazil, Colombia, Kenya, Nigeria, India, Pakistan and Indonesia). For more stories from this trip, sign up for my newsletter (edwell.substack.com) and follow me on LinkedIn. 🌏