🌱 The Biggest School Operator You've Never Heard Of

5 lessons from the Citizens Foundation & 280,000 learners in Pakistan.

Did you know there is a nonprofit successfully running 1,833 schools in one of the world’s most difficult contexts?

The Citizens Foundation (TCF) started in 1995 and scaled - despite constant challenges in Pakistan (devastating floods in 2010 and 2022, militancy from Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, the US invasion/war in neighboring Afghanistan from 2001-2021, a coup and martial law 1999-2002, and inflation currently at a 58-year high).

The Economist called them “perhaps the largest network of independently run schools in the world.” They are a rare success story in the world’s 5th largest country (239 million people!) But outside of Pakistan, few people know about TCF.

When I visited TCF in Karachi last week, 5 methods stood out that we can learn from:

1. Mobilize Collective Philanthropy Through Zakat.

TCF’s co-founders built a model based on collective leadership that started with six friends. As co-founder Ateed Riaz told me, in the early 1990’s, Karachi faced high levels of violence. When he and his friends attended dinners or social events, they often heard elites complaining. But they liked to act, not complain (they had all been involved in college student unions or public interest litigation).

So this group of six decided to do something. First, they started piloting ways to train local artisans to generate a fairer income. They also visited hospitals to explore solutions in healthcare. But they decided education was the most effective lever for them to transform the country. Six co-founders put in their own money to fund TCF’s first five schools, which they built in informal settlements in Karachi.

As Ateed explained, what helped was that they previously invested in real estate together - so they built trust and knew each other’s ways of working. All the co-founders were 40-50 year old entrepreneurs and business leaders, so they had youthful idealism and entrepreneurial mindsets. These factors were key as they embarked on the ambitious venture of building schools.

Their first goal was to build 1,000 schools. To raise the massive resources required, the co-founders developed a unique fundraising model where thousands of donors feel like co-creators of TCF. As Ateed explains, for the co-founders, “we were custodians of the organization…except it did not belong to us.”

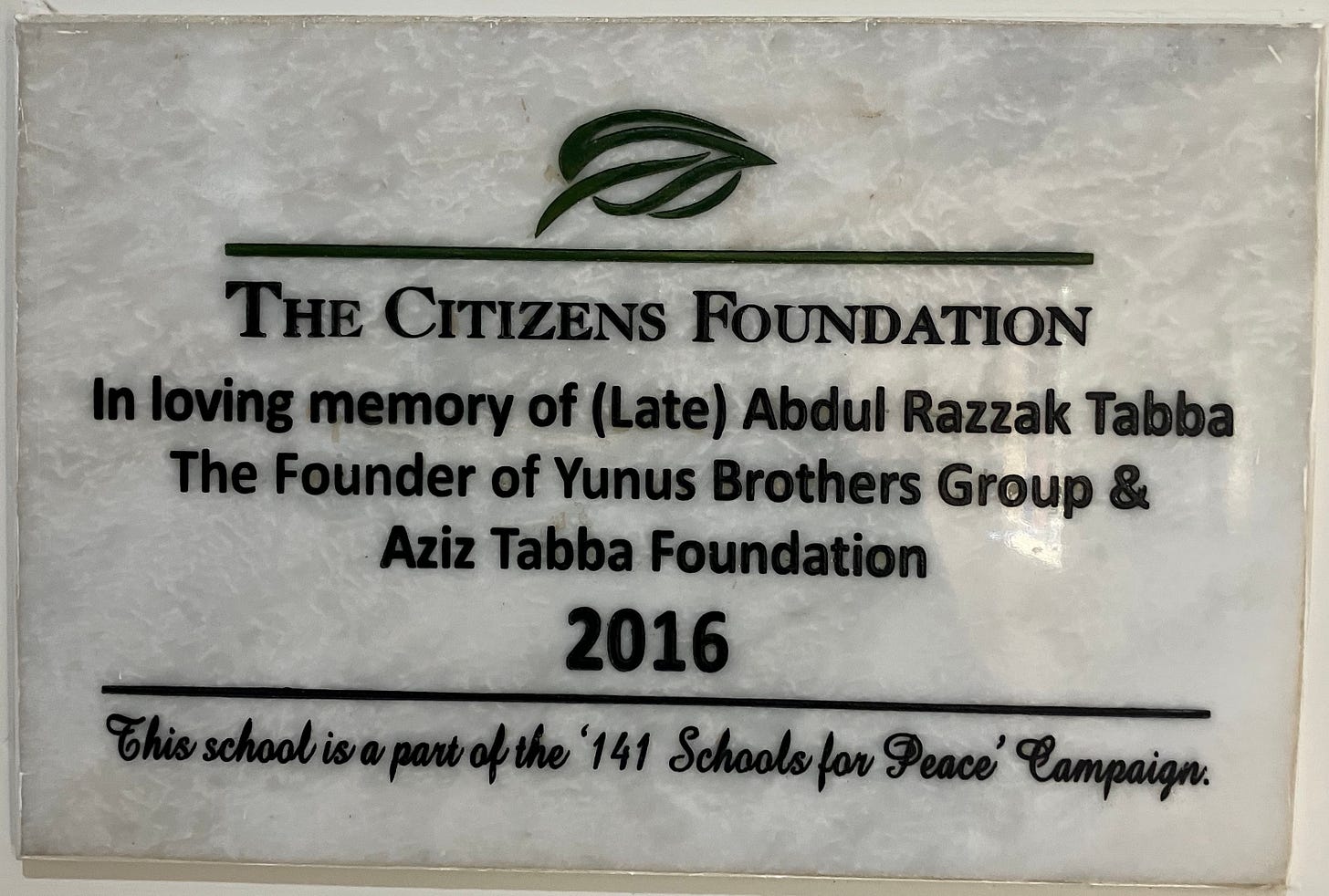

Some supporters donate their land for new school sites. This could be in their ancestral village, or sometimes through a corporate donation (the school I visited was in an industrial area, with land donated by a family that owns the factory next door). Others donate money for annual school operating costs.

TCF grows a network of committed volunteers who donate and mobilize other donors. About half their funding is from within Pakistan and half from outside Pakistan - mostly the Pakistani diaspora (primarily in Canada, the US, UK, UAE and Australia), along with others like UBS Optimus Foundation and the Gates Foundation. As VP Zia Akhter Abbas told me, TCF uses language of a “movement” and a TCF “family” - and so many people want to be part of TCF because it gives them “hope” when there are so many depressing challenges in Pakistan.

TCF was also able to mobilize so many donors because of zakat - the culture of philanthropy in Islam. Muslims are expected to give away at least 2.5% of their wealth to social causes (similar to tithe in Christianity or Judaism).

These methods enabled TCF to raise $55 million USD in 2022.

2. Adapt Corporate & Military Management Styles.

Because TCF’s co-founders were all entrepreneurs or CEO’s, they viewed launching TCF as they would any other business - they hired professional managers and held them accountable to reach certain outcomes.

They particularly valued seasoned leaders who had led large multi-national teams at corporates. TCF’s current CEO was previously a senior leader at Exxon-Mobil and other oil companies, while current VP’s led at Shell, P&G, and banking companies. Out of seven executives, two have education expertise.

Due to Pakistan’s particular socio-political context, they also hired managers from the military. TCF’s schools are divided into regions and sub-areas; all Regional Managers and Area Managers are former military officers. Also, TCF’s 1st CEO was previously a general and CEO of a steel company owned by the military; the 2nd CEO was a former general.

Though some might criticize this (having a corporate/military mentality in schools is probably not what educationists like Paulo Freire had in mind), I actually think it is part of what made TCF succeed within Pakistan’s unique context. As Ateed Riaz admits, having an ex-military CEO and Regional Managers meant that when TCF inevitably faced challenges related to powerful militants, feudal landowners, or tribal leaders, TCF’s leaders knew how to react and were able to protect TCF as it grew. As Ateed describes, in “the politics of the country, there is no single political party that stretches from north to south and east to west. But if you look at the Army…their presence” goes across the whole country.

Many school founders I know have worked in education all their lives. But TCF’s founders had careers in business before they decided to tackle education. Neither approach is necessarily better. But TCF showed me that we need more educationists coupled with expertise about how to manage and scale a large organization with a strong culture, across many complex geographies. TCF now has over 19,000 staff, and the skill to manage such a large team can come from outside education.

3. Reduce Costs to Design for Scale.

TCF also has a relentless focus on keeping costs as efficient as possible while still ensuring quality:

Teacher training happens at area hubs across Pakistan instead of one central headquarters (to reduce transport).

Most teacher support does not happen in training. Area Education Officers each oversee about 40 schools and they are the primary contact supporting schools to improve.

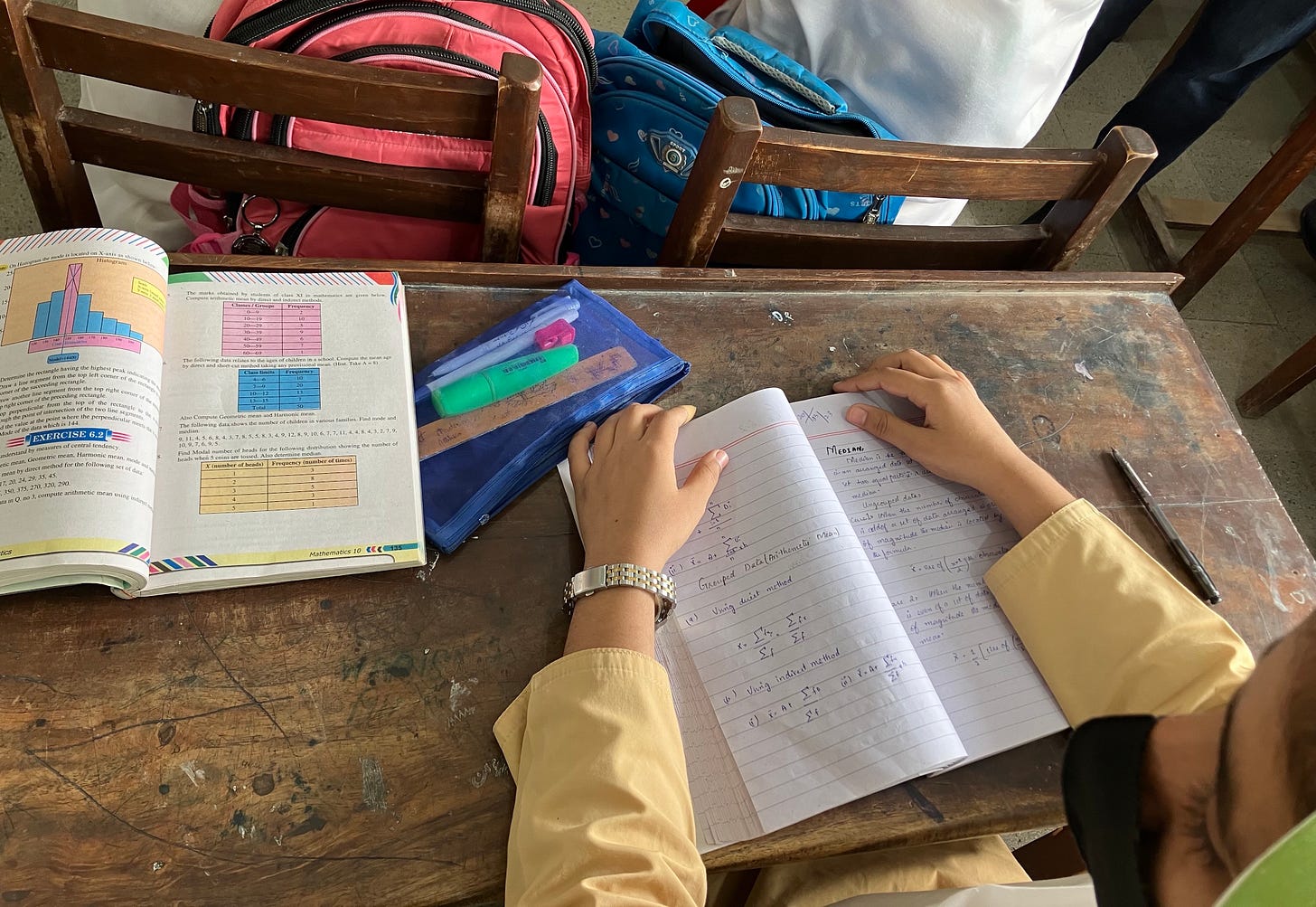

Teachers use scripted lessons (what TCF calls teacher guides) - printed books that tell them what activities to run, student workbooks to use, assignments to give, etc. This reduces the training necessary for a teacher to deliver the model with quality.

Students mostly use books developed by TCF’s own in-house publishing department (TCF also sells these to other schools and gives free copies to government leaders). This allows TCF to print more cheaply with economies of scale and minimize purchasing expensive books from other publishers.

TCF offers transport to many teachers (who are all female), which keeps them safe when going to/from work. They try to make the routes as efficient as possible so it is affordable to teachers.

The cost to educate a student is 2,700 Pakistani Rupees monthly (~$10 USD). All students pay fees, but the amount is on a sliding scale based on their family’s income and how many children they send to TCF. TCF offers subsidized uniforms to some students, and rents books to students who can’t afford to buy.

According to VP Shazia Kamal, TCF teachers make a base salary of roughly 17,000 Pakistani Rupees monthly pre-tax - which is about $60 USD monthly (on date of this article’s publication). They receive higher salaries depending on their subject area.

(I spoke to two former TCF staff who argue that this is a way TCF perpetuates teachers living in relative poverty. TCF teachers make roughly $2 a day, when the World Bank’s poverty line is $2.15 a day. However, TCF staff told me that teachers at other private schools in Pakistan typically make roughly $1-$1.5 a day.)

4. Use Evidence to Influence Government.

According to a co-founder, originally TCF was explicitly “apolitical” and did not get involved with government. But they started adopting government schools in 2016 in Punjab province (similar to a state), and later in Sindh province. They still do not associate with particular politicians or political parties, but they do partner with government agencies.

Their theory of change now is to use their own schools as a proof point for how government can deliver a higher-quality education at a cost that fits within government budgets.

TCF runs a total of 1,833 schools, and out of these, 359 are government partnerships. They have three types of schools:

They manage private schools.

They build schools and operate them with per-child subsidies from provincial/state governments.

They adopt and run existing schools handed over by the government - also with a per-child subsidy from governments.

TCF influences government policy in a few ways. A VP, Riaz Kamlani, was invited to be Chairperson of Punjab Examination Commission - which oversees reforms to the high-stakes exams for all students in Punjab (a province with over 22 million children).

When Pakistan’s central/federal government was going through a process of creating a common national curriculum, TCF staff joined key committees to offer technical support. They also share TCF-written student workbooks so that government leaders can use those as models.

TCF also exerts its influence on the public debate through the media. As Zia Akhter Abbas told me, TCF aims to accelerate “a fact-based conversation about education.”

5. Commit to Strong Learning Outcomes.

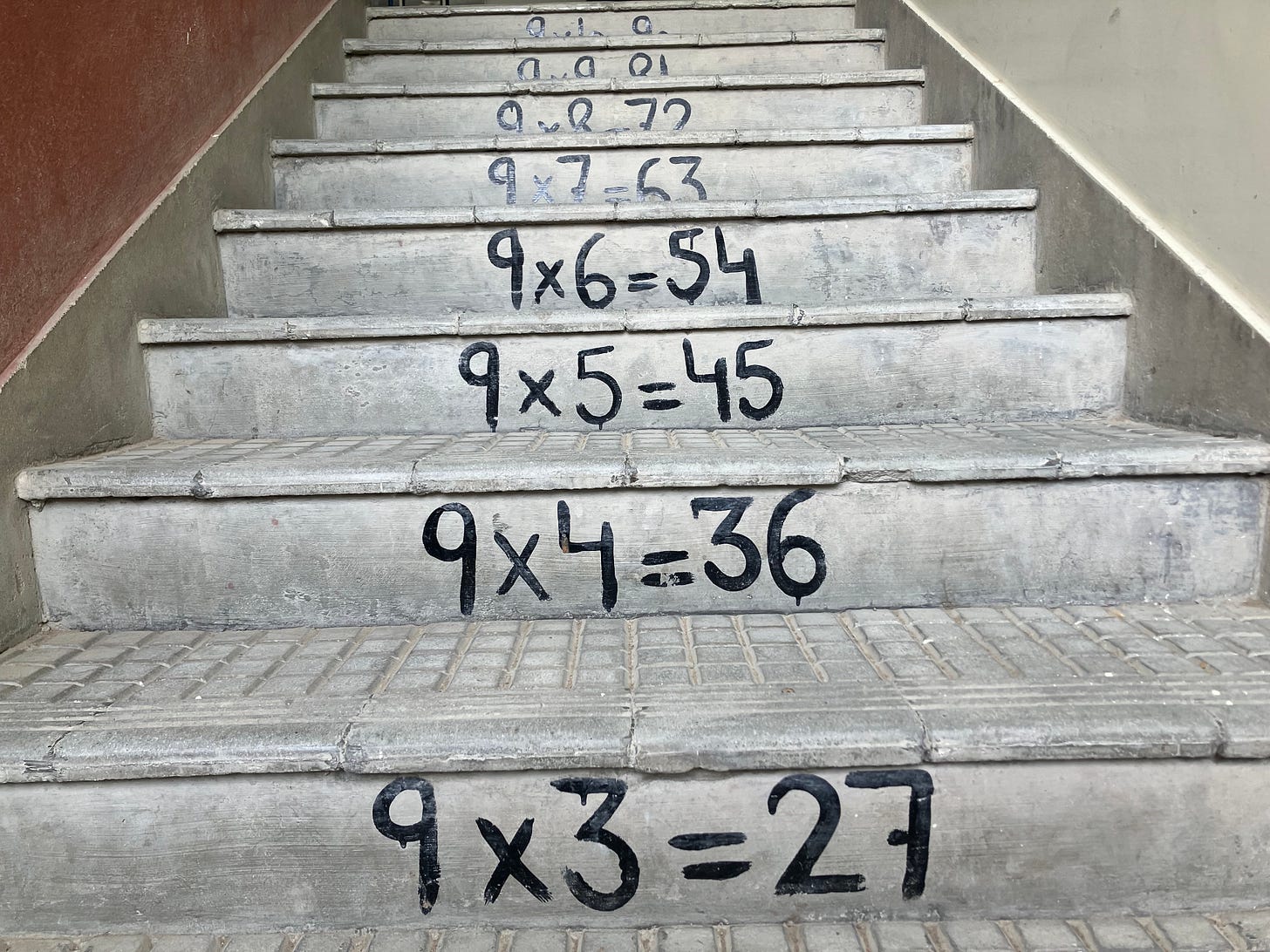

Most important to TCF’s success is that through all of this, they focus on equipping students with strong skills in literacy, numeracy, and other subjects. This culture pervades the organization.

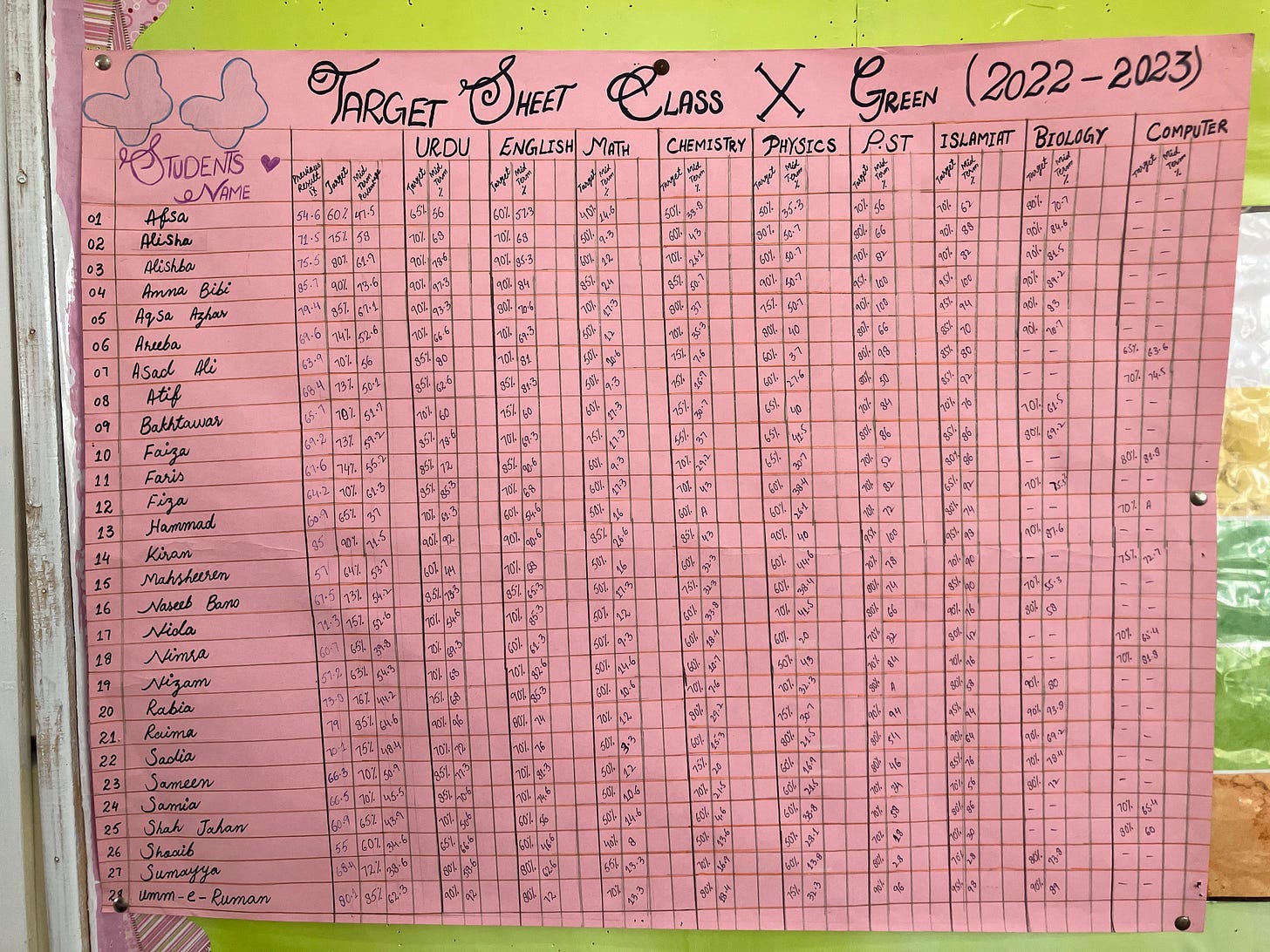

One way I saw this was in the School Scorecard - which ensures all staff have clear goals to work towards. An evaluation team visits each school once a year to assess the principal. They compile this along with data on a range of indicators (teacher quality, student assessments, etc), to generate a Whole School Index Scorecard. Then the Area Education Officers (AEO’s) use it to help the school make a school improvement plan for the next year. AEO’s drop by for surprise visits to each school (the school I went to has two visits a month). They observe lessons, observe students, interact with students to sample whether they are learning, and coach principals and teachers to grow. AEO’s always refer back to the scorecard, which has indicators for teaching quality and student assessments.

These methods translate into results for 280,000 learners each year. For example, I met Doulat, a grade ten student. He grew up in Balochistan, a province bordering Afghanistan that has experienced ongoing insurgency and violence. At age ten, Doulat moved to Karachi alone, so that he could attend a TCF school. He sees his parents less than two months a year, when they visit on breaks from their work farming wheat; the rest of the time, he lives with distant relatives.

When I met Doulat, he spoke confidently in Urdu and English, asked thoughtful questions, and was busy preparing for important year-end exams. His story showed me how much parents and students value a TCF education - and that they will do whatever it takes to get one because they know it will change the lives of the next generation.

To learn more about TCF, read:

A book with interviews from TCF staff and stakeholders, written by a former board member and a TCF alumni.

UN case study of TCF’s methods for enrolling girls. World Bank piece on TCF’s methods for training school leaders. Profile video from Skoll Foundation.

Article about TCF and Pakistan’s PPP’s in The Economist. Essay by TCF principal in The Guardian.

**BONUS - other things I loved:

While many schools in Pakistan try to teach in English (though most students don’t speak it), TCF teaches in Urdu - with English as a subject in upper grades.

They build water filtration plants on certain school sites that provide clean water at affordable cost to 38,000 local community members daily.

Their head office has a supervised childcare area where staff can drop their children while they work.

They run Aagahi, a program to teach literacy to adults that reaches over 20,000 a year - including factory workers who attend class on factory floors.

All teachers and principals are women! This helps parents feel more comfortable sending their daughters to school.

💫 This is part of my journey to write a book about pioneers of systems change in the Global South's education bright spots (Brazil, Colombia, Kenya, Nigeria, India, Pakistan & Indonesia). For more stories from this trip, sign up for my newsletter (edwell.substack.com) and follow me on LinkedIn or Instagram @katpattillo. 💫

Hi kat, as you said you will support as far as it is possible. I want to be a writer and also want to live in USA. It's my parents dream. And I will work on achieving it constantly. I still am not that educated. I know nothing still. I wish to learn more and for that I want your support. Just be my Voice let the funders of TCF know about me and help me for getting higher education.

Thank you

Dear kat I want to get high education and also I want to have support from you. I hope u will support me for getting higher education. Believe me it's my dream to go USA and get good education there. My parents are very poor they can afford nothing. I just want you to support me.