📜 Wisdom from the Oldest Schools in the Global South

Advice from leaders who pioneered education access 7,000 years ago.

For jobs/funding, read my LinkedIn posts. With feedback, hit reply. - Kat

Many assume the world’s first schools were in the Global North (like University of Oxford founded in 1096) — and complain about how far Global South schools have to go to solve the learning crisis. But while the oldest European schools started around 600-700, India and China actually had formal schools long before then.

Across the Global South for over 7,000 years, leaders built groundbreaking education models with useful lessons for anyone trying to improve education systems today. This article reflects on this history to share 7 insights on education, drawing from religious centers in India, Tunisia, Morocco, and Pakistan, griots in Mali, scribe training in Egypt, exams in ancient China, the Aztec’s Tēlpochcalli & Calmécac schools, and the first universities in Latin America, Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. They show us the power of:

Apprenticeships

Identity/values

Self-directed learning

Stories

Assessments

Activists

Hubs for knowledge exchange

1. APPRENTICESHIPS equip students to improve through practice.

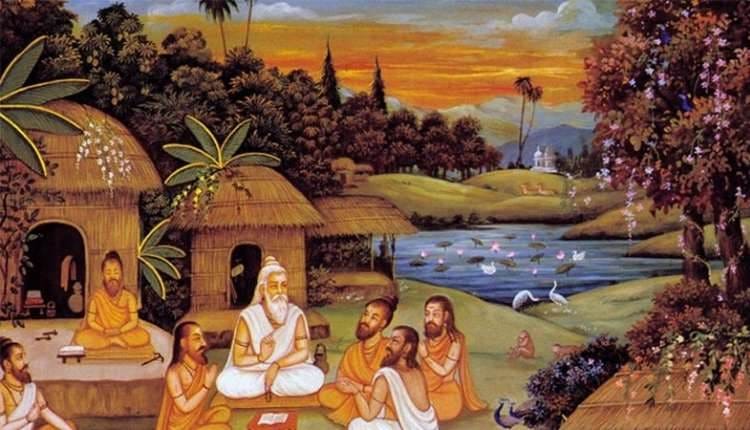

Gurukul in India are likely the oldest formal education system in the world, as they started around 5000 BCE. They passed down knowledge and practices to children from the Vedic tradition (the foundation of Hinduism), with subjects such as geography, botany, environmental studies, yoga, and meditation. Students learned through oral lessons and apprenticeship, because they lived at the home of their teacher (called a Guru). Students learned values, culture, and discipline by applying skills; for example, they did household chores to maintain clean religious spaces. As a result of the Gurukul system, schools existed in almost all villages across India by the 1700’s (but were dismantled by Britain when it colonized India in 1858).

2. Schools develop citizens with shared IDENTITY and values.

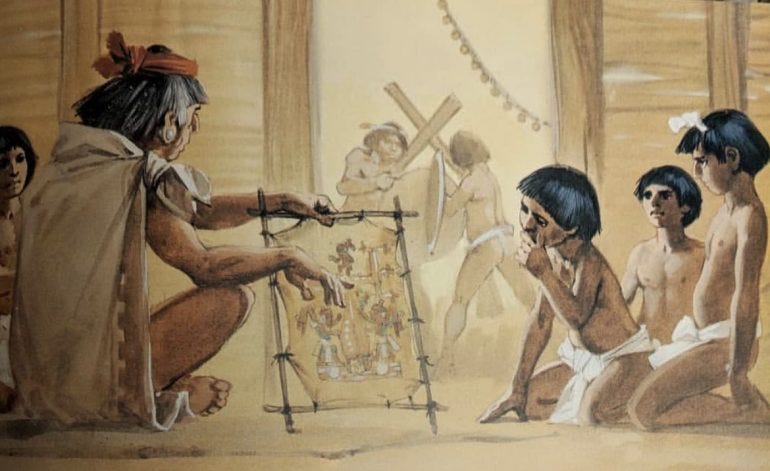

In the 1300’s, the Aztec Empire ran Tēlpochcalli and Calmécac schools, in what is now Mexico. Calmécac trained the sons of nobility and future priests. From age 5, boys learned subjects such as reading, writing, theology, geometry, and political skills. While Calmécac were for elites, Tēlpochcalli were in every village for commoners. From age 15, boys learned military skills, farming, hunting, and trades. According to Aztec documents, the system aimed to teach students:

“How they are to live, how they are to obey people, how they are to respect them, how they are to surrender to what is…right.”

Girls attended separate schools focused on housekeeping. From their families, children learned huehuetlatolli — the “words of the old” — which were their society’s beliefs about important topics such as life, death, myths, values, ceremonies, rituals, and their calendar. According to Muy Interesante, children also went to “the ‘cuicacalli’ or ‘house of song’, where they learned to play musical instruments, dance and sing.” The Aztecs show us that schools play a critical role in shaping identity. The Aztecs are also remarkable because they expanded FREE universal secondary education to every child, long before the rest of the world.

3. SELF-DIRECTED learning leverages intrinsic motivation.

Three universities started within the span of 250 years, and all had a mosque with a madrasa (center for Islamic learning) where scholars had circles to study and share knowledge: Ez-Zitouna in Tunis, Tunisia in 737, Al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, Morocco in 859, and Al-Azhar in Cairo, Egypt in 970. Students learned subjects such as Islamic law, Arabic grammar and literature, Islamic astronomy, and Islamic philosophy. In Al-Azhar’s model, students did not follow a prescribed schedule; instead, they were encouraged to attend lectures they were curious about and dialogue with other students to progress their skills. As Tarek Osman explains:

“Azharite students were expected…to roam the ‘pillars’ of the grand mosque, which was the primary campus where sheikhs typically lectured twice a week…They were expected to find a place in a ruwaq (alley) where students with different interests would gather.”

People are more likely to act based on intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation. Although there are certainly benefits from a school having a schedule, these universities show that there is also power when students guide their learning. Also, Al-Qarawiyyin is the oldest continuously operating university in the world (AND it was started by a woman!) According to Daily Sabah, “scholars and students from all over the Muslim world visited and enrolled…Fatima's ideas and vision influenced many universities across Europe.”

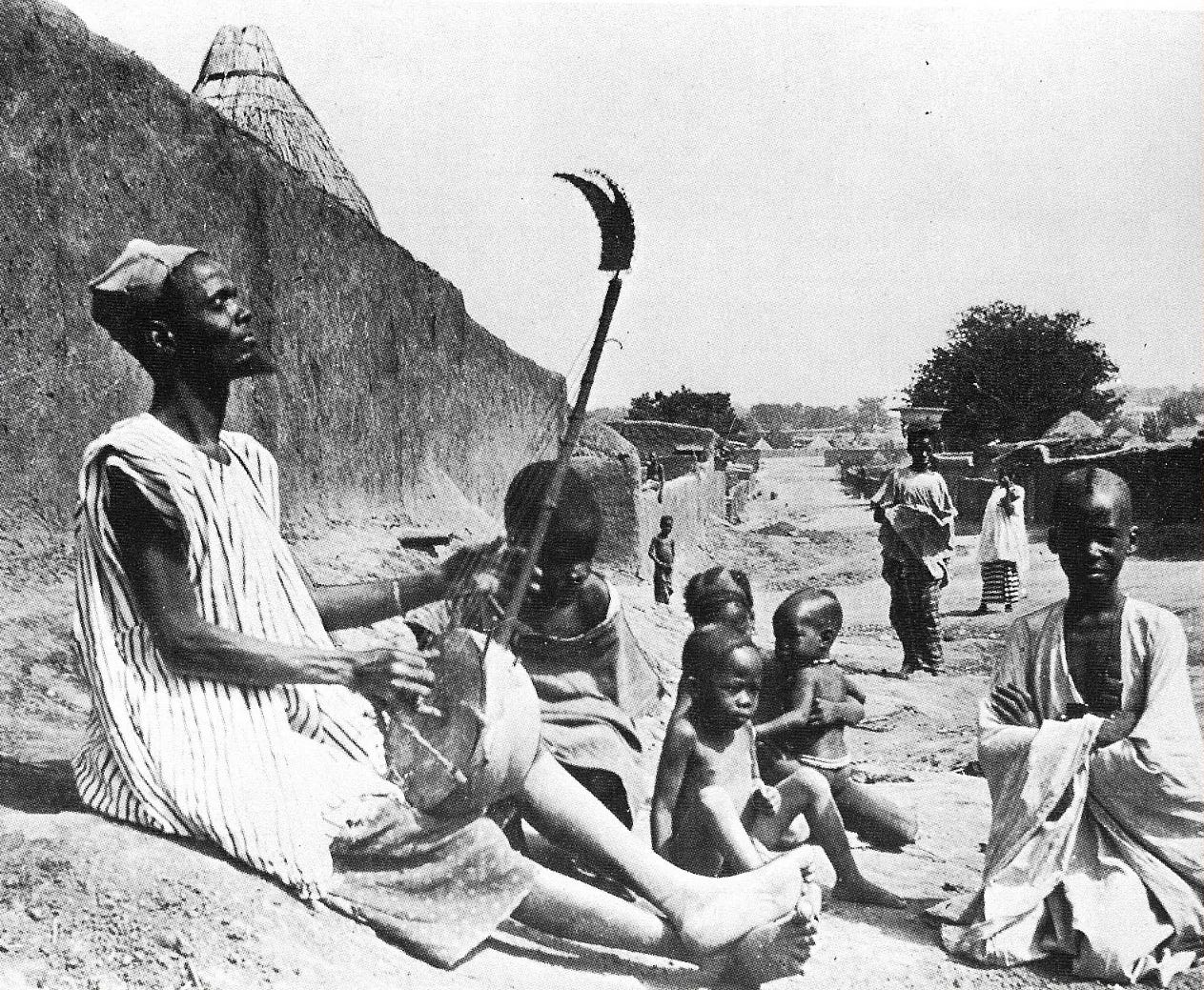

4. STORIES are powerful tools for teachers.

Humans started to speak around 1.75 million years ago and pass down knowledge around 400,000 years ago, through storytelling, songs, and chants (that was when humans started spreading techniques for how to start a fire). A key moment in this evolution were West African griots, who originated in the 1200’s. Part-historian, part-musician/ storyteller, griots preserved and taught information through an oral tradition of poems and songs. Griots emerged across the Mali Empire (which covered from current-day Senegal and Mali, to Niger and Chad). When a child was born into a griot family, from the ages of 8-18 they learned a repertoire of hundreds of stories and songs (such as the Epic of Sundiata, which taught children the story of the founder of the Mali Empire.)

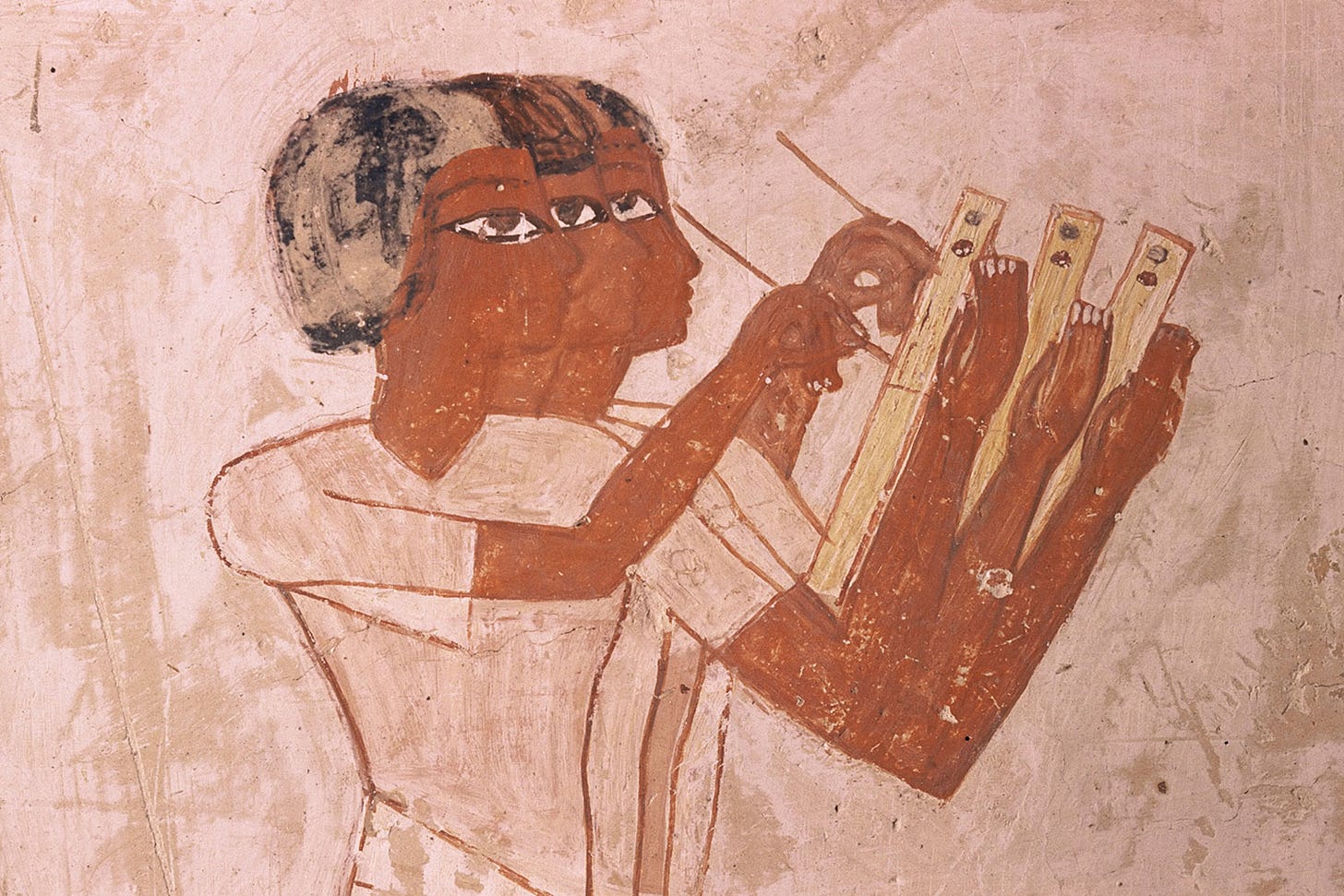

Long before the Mali Empire, ancient Egypt had its own tradition of education through storytelling. Around 3100 BCE, Egyptians developed hieroglyphs, one of the first forms of writing. They had an entire set of stories designed to teach key information, called Wisdom Literature. Around 2000 BCE, they also started special schools, called stables, where young boys learned how to read and write to gain the title of scribe. Scribes used ink, a reed brush, and papyrus (a form of paper) or pieces of clay pottery, to practice writing and copy Wisdom Literature. Scribes also learned skills like how to record a census or weigh expensive metals.

5. ASSESSMENT can reward results.

China has what many consider to be the oldest primary or secondary school in the world: Shishi High School, founded around 143 BCE in Chengdu. But more information exists about a school founded later in ancient China — the Temple of Confucius in Hanoi, Vietnam. Founded in 1076 as a training hub for the ancient Chinese empire, the first students were royalty, aristocracy, and elite bureaucrats. The Academy taught them to rule based on Confucian ethics and practices, with skills in calligraphy, literature, poetry, and mathematics. To graduate, they had to pass notoriously competitive imperial exams, which selected who would join China’s civil service based on merit.

Both Shishi and the Temple of Confucius point to the powerful role of high-stakes assessments. Countries that were part of ancient China (now Vietnam, South Korea, and China) have a long history of intensive summative exams, and this is part of why most have high scores on international education benchmarks like PISA. Although there are definitely drawbacks to such an approach, it indicates how assessments can pressure a system towards stronger learning outcomes.

6. Schools are sites for political struggles and can train ACTIVISTS.

Three universities show how schools educate activists who shape the course of politics and history. Schools can be both hubs for resistance movements and training grounds for the elite establishment. The first university in Latin America, National University of San Marcos, started in Lima, Peru in 1551. It is the oldest continuously operating university in the Western Hemisphere. 21 Presidents of Peru were alumni or professors, and it has long had important protests. In 1909, students protested against Peru’s dictatorship, and in 1952, they held a strike against the Odría dictatorship. When Richard Nixon (then US Vice-President) visited in 1958, students protested against his administration’s policy in Latin America. One graduate was Mario Vargas Llosa, the first Peruvian to win a Nobel Prize. As he notes,

San Marcos “was one of the rare institutions [with] a spirit of resistance, democracy…a dissatisfied, rebellious institution, where a different future for our country had been dreamed of.”

Another site of political struggle was the oldest university in Asia, University of Santo Thomas, founded in Manila, the Philippines in 1611. It played a key role in World War II, when the Japanese occupied and used the university’s campus as an internment camp for over 400 enemies living in the Philippines (mostly Americans). In Cairo, Al-Azhar has also played a critical role in Egyptian politics.

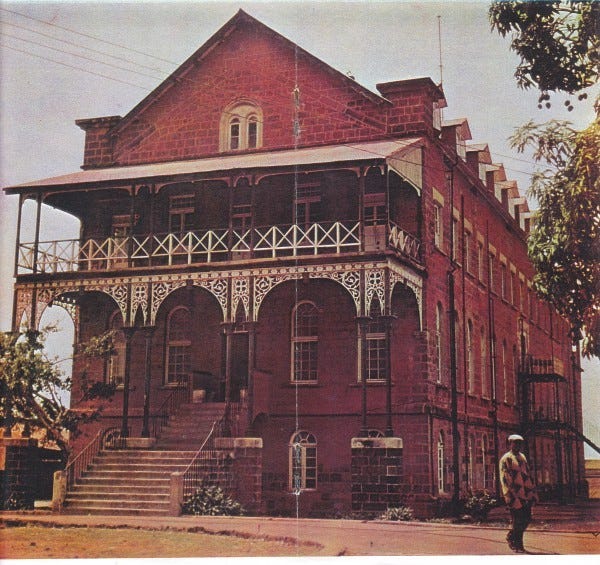

Finally, many consider the second university in Sub-Saharan Africa to be Fourah Bay College, founded in Freetown, Sierra Leone in 1827. Because of this college, Freetown was often called the “Athens of Africa.” According to UNESCO,

“products of Fourah Bay College were leading figures in decolonization political activism and were political leaders in the newly independent African States.”

Fourah Bay was founded by British missionaries to educate freed slaves who were relocated to Freetown, to be clergy and civil servants. Alumni went on to play important roles in history, such as the founder of the first secondary school in Nigeria and Ghana’s first Minister of Education post-independence. But unfortunately, the college was also part of a larger political process under way at that time in Sierra Leone, which was colonized by the UK. As UNESCO claims,

“Freetown began to be visualized in the words of one historian, as an ‘experiment in social engineering’ of Western civilization in ‘dark Africa’. The spread of Western education stood at the center of the experiment….Fourah Bay College was the laboratory for experimenting with the transfer of Western governance ideas, religion, political organization, and public service bureaucracy.”

7. Schools are HUBS for knowledge exchange across regions.

The University of Sankore started in 1350 as a mosque with a center for Islamic learning attached, in what is now Mali. It was founded by Mansa Musa, head of the Mali Empire (who some consider the richest person in history) after he visited Cairo and decided to create a center for Islamic learning in Timbuktu. Timbuktu was already a hub of trading routes for salt and gold, but University of Sankore made it into a magnet for scholars and students from across the Islamic world (at its peak, it had over 25,000 students). It also became a center for the production of manuscripts and had libraries with over a million books. It is remarkable how Musa used a university to make this area at the edge of the Sahara desert, one of the world’s most important centers for Islamic teaching and scholarship.

Finally, centers for Vedic/Hindu and Buddhist learning started in Taxila in 600 BCE and Nalanda in 400 BCE. Taxila was located in modern-day Islamabad, Pakistan, which was a major city in ancient India. It drew students to study subjects such as Buddhism, hunting, archery, law, and medicine. According to Buddha Prakash:

Students “traversed the vast distances of northern India in order to join the schools and colleges of Taxila…Brahmana youths, Khattiya princes and sons of setthis from Rajagriha…and other places went to Taxila for learning the Vedas and eighteen sciences and arts.”

A university in Nalanda started around the same time in what is now Northeast India. It was a hub for Buddhist learning and hosted monks and scholars from China, Tibet, and Korea. Both Taxila and Nalanda show how a university can attract experts from across a region to learn and share their knowledge.

Thank you to Audrey Cheng for ideas and editing that shaped this article.

A reader sent me another neat example - Gondishapur University in Iran. It was "the intellectual center of the Sasanian Empire" and a hub for the study of medicine and theology in the 6th and 7th centuries: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy_of_Gondishapur